Rad Resilient City Initiative

A Local Planning Tool to Save Lives Following a Nuclear Detonation

The purpose of the Rad Resilient City (RRC) Initiative is to provide cities and their neighbors with a checklist of preparedness actions that could save tens of thousands of lives following a nuclear detonation through adequate protection against radioactive fallout. The Fallout Preparedness Checklist converts the latest federal guidance and technical reports into clear, actionable steps for communities to take to protect their residents. The checklist and supporting materials reflect the shared judgment of the Nuclear Resilience Expert Advisory Group, led by the Center for Biosecurity of UPMC (now the UPMC Center for Health Security) in 2011. This interdisciplinary panel included government decision makers, scientific experts, emergency responders, and leaders from business, volunteer, and community sectors.

Nuclear terrorism is a real and urgent threat, according to assessments by the US and other governments and by independent nongovernment experts.1-3 Detonation of a crude nuclear bomb in a thriving city could kill tens of thousands of people, dislocate millions, and inflict immense economic and social damage.4 Even if prevention fails, US cities need not be resigned to a worst-case toll of injuries and deaths. Casualties due to exposure to radioactive dust and debris—that is, “fallout”—could be minimized if the public immediately sought adequate shelter and awaited further information before evacuating.5,6 Federal modeling of a 10-kiloton groundburst in Los Angeles suggests that if everyone at risk of exposure to dangerous fallout quickly went into a shallow basement or an equally protective place, then 280,000 lives could be saved.7

Cold War memories and movies have shaped popular ideas about nuclear weapons and created a fatalistic outlook about nuclear terrorism that still persists. But the terrorist scenario of a low-yield explosion in a modern urban setting does not, by any means, approach the wholesale destruction imagined in an all-out nuclear war. This document dismantles these and other misconceptions that may be held by communities and their leaders, including the following:

- Not all casualties due to a nuclear detonation are predetermined; those from exposure to fallout can be prevented.

- Quickly sheltering in the right place—not fleeing the area—is the safest thing to do after a nuclear attack.

- People can protect themselves immediately following a detonation and should not wait for emergency professionals to help them.

The Fallout Preparedness Checklist provides mayors, county executives, city administrators, emergency managers, public health and safety officers, business executives, heads of volunteer- and community-based groups, and other local opinion leaders with a unified vision and concrete implementation plan for fallout preparedness. Recognizing that implementation will take time, the checklist balances the practical and the “perfect,” and it puts actions in order of priority. The order in which the actions are presented reflects the expert advisory group’s judgment about what activities should be tackled first. This appraisal includes a measure of which steps are prerequisites for others and which exhibit a high degree of complexity and expense. A high-level summary of the checklist is below.

Rad Resilient City Preparedness Checklist Actions

- Obtain broad community backing and understanding of nuclear incident preparedness to sustain the program over time. Fallout preparedness requires commitment across a community. There is no single entity that can deliver this public service. Sound emergency management structures and strategies are essential, but so too are efforts by businesses, schools, nonprofits, and average citizens. A coalition of diverse stakeholders can help overcome the political and popular resistance to planning for an unthinkable incident like a nuclear detonation.

- Conduct an ongoing public education program to inform the public about the effects of a nuclear detonation and how they can protect themselves. In a “no notice” nuclear detonation, people need to be empowered beforehand with the knowledge that the most effective action they can take is to find adequate shelter immediately. Following a detonation, it will be difficult or impossible to issue fallout warnings in the areas that most need them due to destruction and disruption of the communication infrastructure.

- Enable building owners and operators—from individual householders to skyscraper managers—to assess shelter attributes and to teach others. U.S. studies show that people spend almost 90% of their time in enclosed buildings. Homeowner associations, commercial building managers, public building operators, faith-based entities, and school facility administrators can adopt and promulgate shelter rating information so that occupants of all types learn which structures and which places within them provide the most safety.

- Strengthen the region’s ability to deliver actionable public warnings following a nuclear detonation through well-chosen technologies and organizational procedures. Assuming a degraded communication infrastructure in certain locales, jurisdictions need to devise creative ways to deliver fallout warnings (eg, blending radio broadcasts with text-based messaging) and to have pre-scripted, scientifically based public messages about protective actions. City leaders should not wait until after an incident to decide who should authorize the release of a fallout warning and what it should say. Time delays can result in preventable deaths.

- Establish a rapid system for mapping and monitoring the dangerous fallout zone to specify which residents need to take what protective action. Knowing the fallout “footprint” (from on-the-ground monitoring) can vastly improve guidance about which residents need to evacuate, how quickly, and which routes present the lowest possible exposure. It will be just as important to communicate to people for whom fallout is not a health risk. Unnecessary evacuation strains resources and infrastructure needed for people in high-risk areas.

- Develop planning strategies and logistical capabilities to support a large-scale, phased evacuation. At a certain point in time, some people will need to transition from their protective shelter to a place of greater safety. This complex task calls for advance planning. People still exposed to significant radiation levels and those suffering from life-threatening injuries will need to leave the area sooner than others, and their departure could be impeded by impassable roads and heavy demand.

- Integrate, test, and conduct training on the above elements of a comprehensive fallout preparedness and public warning system. Unless people have a chance to train and to practice in routine—that is, nonemergency—time, they will be less likely to perform well when it really matters.

How Does a Jurisdiction Benefit from Adopting the Preparedness Checklist?

Successful adoption of the Fallout Preparedness Checklist can produce significant gains for communities. The collaborations essential for nuclear terrorism readiness can have spillover effects for other complex disaster management matters. A program for fallout preparedness—where the ability to shelter for at least 1 to 3 days is central—builds on elements of an all-hazards framework and extends that framework so that it truly becomes comprehensive in the ability to address nuclear terrorism. Moreover, steady implementation of the checklist can create momentum for cities and their neighboring areas to tackle other difficult nuclear response and recovery issues like the surge in demand for medical services, search and rescue capabilities, and the sheltering of mass, displaced populations. Lastly, and most important, after an actual nuclear detonation, having implemented this checklist could save tens of thousands of lives.

RRC workbook: Full formatted | Printer friendly PDF

Rad Resilient City Project Team

Monica Schoch-Spana, PhD, Senior Associate

Ann Norwood, MD, COL, USA, MC (Ret.), Senior Associate

Tara Kirk Sell, MA, Associate

Ryan Morhard, JD, Associate

Nuclear Resilience Expert Advisory Group

The Nuclear Resilience Expert Advisory Group (NREAG), is a panel led by the Center for Biosecurity of UPMC (now UPMC Center for Health Security) that comprises government decision makers, scientific experts, emergency responders, and leaders from business, volunteer, and community sectors. The panel was integral to the development of the Rad Resilient City Checklist.

Rad Resilient City Initiative

Rad Resilient City Preparedness Checklist

Full formatted document • Printer friendly PDF

How Can Concerned Cities and Regional Partners Best Prepare for Radioactive Fallout?

The Fallout Preparedness Checklist is a tool for designing and implementing a fallout preparedness program for cities and their regional partners. Coupled with each action is a set of implementation tasks. Because implementation will take time and jurisdictions have limited resources, the checklist attempts to balance the practical and the “perfect.” The order in which the actions are presented reflects the Expert Advisory Group’s judgment about what activities should be tackled first. This appraisal includes a measure of which steps are prerequisites for others and which exhibit a high degree of complexity and expense.

Rad Resilient City Preparedness Checklist

Click each action to see associated tasks

Action 1: Obtain broad community backing and understanding of nuclear incident preparedness to sustain the program over time.

Action 2: Conduct an ongoing public education program to inform the public about the effects of a nuclear detonation and how they can protect themselves.

Action 3: Enable building owners and operators—from individual householders to skyscraper managers—to assess shelter attributes and to teach others.

Action 4: Strengthen the region’s ability to deliver actionable public warnings following a nuclear detonation through well-chosen technologies and organizational procedures.

Action 5: Establish a rapid system for mapping and monitoring the dangerous fallout zone to specify which residents need to take what protective action.

Action 6: Develop planning strategies and logistical capabilities to support a large-scale, phased evacuation.

Action 7: Integrate, test, and conduct training on the above elements of a comprehensive fallout preparedness and public warning system.

Download checklist as PDF • See phased implementation plan

How Does a Jurisdiction Benefit from Adopting the Preparedness Checklist?

Successful adoption of the Fallout Preparedness Checklist can produce significant gains for communities. The collaborations essential for nuclear terrorism readiness can have spillover effects for other complex disaster management matters. A program for fallout preparedness—where the ability to shelter for at least 1 to 3 days is central—builds on elements of an all-hazards framework and extends that framework so that it truly becomes comprehensive in the ability to address nuclear terrorism. Moreover, steady implementation of the checklist can create momentum for cities and their neighboring areas to tackle other difficult nuclear response and recovery issues like the surge in demand for medical services, search and rescue capabilities, and the sheltering of mass, displaced populations. Lastly, and most important, after an actual nuclear detonation, having implemented this checklist could save tens of thousands of lives.

Checklist Action 1: Build Your Support Base

Obtain broad community backing and understanding of nuclear incident preparedness to sustain the program over time.

Fallout preparedness is a broad community concern. There is no single entity that can deliver this public service. Sound emergency management structures and strategies are essential, as is expertise in radiological control, but so too are efforts by business, schools, nonprofits, faith-based organizations, and average citizens.

Tasks

Task 1.1—Cultivate leadership behind the goal of community preparedness for fallout.

Mobilizing a community to confront a potential nuclear detonation will require a political catalyst—whether the jurisdiction’s chief executive, an issue champion with the expertise and organizational legitimacy to promote readiness, or a disaster planning body that can marshal a broad base in support of nuclear preparedness.25 Such leadership is necessary to overcome both active and passive resistance to advance planning for a nuclear emergency. In general, people tend to discount preparedness because disasters are infrequent and because they believe that such tragedies happen to other people. Some individuals fatalistically assume that little can be done to limit losses, while others reject emergency planning out of fear that more immediate community concerns such as crime and education will receive less attention and resources. The prospect of preparing for a nuclear detonation will likely exacerbate such attitudes. A further complication may be that some authorities wrongly assume that raising the issue of nuclear terrorism will panic people. Past experience, however, has taught us that leaders often underestimate the public’s ability to handle difficult issues.

Task 1.2—Build a fallout preparedness coalition that reflects the entire community and that can maintain support for the issue.

The most realistic and complete emergency plans are developed when diverse government departments and agencies work alongside representatives of the entire community, including leaders from business, public utilities, education, and community- and faith-based groups.28 Inclusion of all community stakeholders in emergency planning conveys the reality that everyone shares in the responsibility for public safety, especially in this case when personal preparedness and protective actions can save many lives. Moreover, inclusive planning strengthens the public motivation for people to undertake planning for themselves and their organizations.28 A partnership approach to emergency management helps to generate resources (eg, ideas, skills, funding, and momentum), advance public understanding and buy-in, and diminish agency turf battles as people coalesce around a common goal—all conditions necessary for successful nuclear response planning.29 Local and regional news media will be essential participants in the fallout preparedness coalition, as they can report on the life-saving benefits of nuclear incident preparedness and on initiatives to educate residents on key protective actions. Existing coalition groups such as citizen corps councils, local voluntary organizations active in disaster, and local emergency planning committees can facilitate needed partnerships with the community. Communities can integrate fallout preparedness into strong, pre-existing coalitions capturing the momentum and commitment that already exists around other hazards and disasters.

Task 1.3—Incorporate radiation professionals and organizations into emergency planning and volunteer registries.

Radiation professionals from both private and public sectors should be fully integrated into nuclear emergency planning. Depending on the jurisdiction, radiation control programs may reside within a public health or emergency management agency or be free standing. Few localities have their own radiation control programs, and most must rely on a state agency (New York City and Los Angeles are exceptions). Volunteer radiation experts from industry, healthcare settings, and research universities are natural allies in carrying out pre-incident public education. Following a detonation, they can relay trusted public warnings and perform population monitoring and other assistance at community reception centers (CRCs), shelters, hospitals, and other locations where potentially contaminated people may converge.30 Jurisdictions should establish relationships in advance with local, state, and/or regional chapters of radiation professional organizations (eg, Health Physics Society, American Association of Physicists in Medicine, Society of Nuclear Medicine, American Society for Radiation Oncology, National Registry of Radiation Protection Technologists, American Nuclear Society, Conference of Radiation Control Directors [CRCPD]). Planners are encouraged to consult CRCPD guidance (2011) on recruiting, credentialing, training, exercising, and deploying such volunteers.30 Some jurisdictions are already incorporating volunteer radiation professionals into preexisting volunteer programs like the Medical Reserve Corps (MRC).

Task 1.4—Recruit community-serving nonprofits and faith-based organizations to participate in emergency planning and to be conduits for reaching vulnerable and underrepresented populations.

People with disabilities and others not traditionally included in emergency preparedness planning—including the hearing- and vision-impaired, elderly people, non-English speakers, ethnic minorities, and communities distrustful of government—are more likely to suffer the impacts of a nuclear detonation because they are not well-positioned to receive, trust, and act on meaningful protective guidance. Agencies and nonprofits serving these groups, however, can provide insights for emergency planning and help promote the dissemination and uptake of critical safety information by their clients. Emergency planners can also benefit from consulting community-serving nonprofits about conditions that might inhibit or facilitate people’s movement to safety, especially among disadvantaged, disabled, or distrusting groups. Community-serving nonprofits and faith-based organizations should also ensure their own continuity of operation by incorporating into their existing emergency plans procedures for reducing the exposure of employees and clients (when on the premises) to fallout.

Task 1.5—Define the problem in local terms by mapping a nuclear detonation’s effects against the region’s unique terrain and inhabitants.

Knowledge of the physical effects of a nuclear explosion as well as attributes of the people and properties in harm’s way can facilitate local planning for fallout protection. Local emergency professionals should take advantage of the state-of-the-art modeling and analysis developed at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, Los Alamos National Laboratory, Sandia National Laboratories, and Applied Research Associates and/or work with their local universities to prepare regional maps that chart the basic anatomy of a nuclear detonation and a range of fallout predictions.6,31 At a minimum, jurisdictions can overlay local and regional maps against projections devised for other cities. At the request of Congress, the DHS Office of Health Affairs has already coordinated efforts to model the effects of 0.1-, 1.0-, and 10-kiloton nuclear yields in New York City, Washington, DC, Chicago, Houston, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. (For illustrative maps using Washington, DC, and Los Angeles, see Buddemeier & Dillon 2009.6) Actual fallout patterns will depend on the real-time conditions of weather, weapon yield and location, and other variables that are hard to predict. Nonetheless, visual representations can raise awareness of the risk environment and set planning expectations—both among emergency professionals and the larger population.

Checklist Action 2: Educate

Conduct an ongoing public education program to inform the public about the effects of a nuclear detonation and how people can protect themselves.

Because a nuclear detonation may be a “no notice” incident and will severely disrupt communications, educating people before an incident on how to protect themselves from fallout is essential. The best strategy to maximize lives saved following a nuclear detonation is for cities and their neighboring communities to implement a coordinated and sustained public education program on fallout preparedness. Pre-incident public education will play a critical role in priming the public to seek shelter rapidly after a nuclear detonation. At its best, a well-executed campaign will also motivate people to take actions beforehand, such as purchasing a hand-crank radio and scouting out familiar buildings that afford the highest protection factors. The following steps rely on empirically based “best principles” for designing a pre-incident public education. Suggested Topics for a Fallout Preparedness Education Campaign outlines key topics that a region may wish to incorporate into its own public education efforts. Resource-constrained jurisdictions may wish to weave fallout preparedness information into an already-existing, credible mass education program for disasters.

Tasks

Task 2.1—Designate a lead agency to coordinate the public education program across stakeholder agencies within the city and with neighboring jurisdictions.

To maximize lifesaving, adjacent jurisdictional plans for pre-incident public education should be coordinated. Science has demonstrated that to be effective, messages should be consistent and delivered by multiple information sources or organizations.26,32,33 The process works best if a single agency is designated as the lead and if stakeholder organizations and jurisdictions commit to a coordinated, long-term strategy. An important task will be to work together to craft key fallout protection messages for use by all members, rather than each group producing a unique message. An example of an inconsistent message would be one group advising residents to stay inside a building for a minimum of 4 hours following a nuclear detonation, while a different organization recommends a threshold of 8 hours. Coordinated messaging is vital in the case of a large city: a person who works in an urban center but who lives in the suburbs needs to hear the same message and to have it reinforced. At best, conflicting information is confusing and, at worst, can undermine the public’s confidence in the efficacy of sheltering and the competence of the organizations issuing messages.

Task 2.2—Focus messages on how people can protect against fallout exposure; using nontechnical language, explain how these actions could save their lives.

While often used in public education campaigns, scare tactics and probability estimates are not effective motivators of preparedness. Instead, people respond to knowledge about what to do, how to do it, and why it will help them.26,32,33 Rather than focus on the likelihood of nuclear terrorism and the horror of radiation injuries, fallout preparedness messages should inform people how to minimize radiation exposure (take shelter), how to do it (know which buildings are best and set aside enough supplies), and why it is important (you can save your life). Educational messages about minimizing fallout exposure can also be linked to other “all-hazard” messages—namely, those about sheltering—and to “teachable moments” where interest in radiation is piqued, such as the March 2011 nuclear power plant emergency in Japan. Familiar, all-hazard preparedness recommendations—have a family disaster plan including ideas for postdisaster reunification; store a supply of food, water, and essential medications; and have a crank or battery-powered radio—all support the goal of extended sheltering in the context of a nuclear detonation and a potentially degraded communication infrastructure. For disaster preparedness in general, emergency professionals recommend that if individuals have not yet set aside any emergency supplies, they should begin with a 3-days’ supply and work up to 1 week and then 2 weeks, once they have adopted a preparedness lifestyle. Larger stockpiles will provide people with more flexibility for unpredictable events and conditions. While people may not need to shelter for more than 1 day to avoid exposure to high radiation levels following a nuclear detonation, damage to critical infrastructure could interrupt access to food and water for several days, maybe more.*

Task 2.3—Disseminate information frequently using multiple modalities (eg, TV, pamphlets, radio, social media) and multiple sources.

Sustained repetition of public education messages is necessary to break through the background noise of everyday life.26,32-34 Also, people vary in what information sources they trust and in how they receive their information. Materials should be translated into multiple languages and the technological needs of those with visual and hearing disabilities addressed. Planning should include the development of resources such as websites for people who may seek more information and the identification of technical experts who are good communicators. Recent evidence indicates that most people trust the local weatherman over other spokespersons. Interweaving informational, social, and physical cues can help reinforce messages about fallout preparedness. For instance, fallout shelter signage serves as a visible reminder of the most important way to protect oneself from fallout. School safety officers could have a parent-teacher association (PTA) group learn about fallout protection, enlist them in the posting of signs at schools, and then work together to identify what is needed to shelter their children safely from fallout.

Task 2.4—Encourage people who have already prepared for fallout to share what they have done with those who are less prepared or who have taken no actions.

The most effective spokespersons for preparedness are people who have already taken action.26,32,33 Thus, the primary targets of a public education campaign on fallout should be those people in the community who typically prepare for other hazards. These individuals can then lead by example, talking about and demonstrating ways to protect oneself from fallout. Drawing on their own in-depth knowledge of the community and its subgroups, these preparedness champions can develop innovative ways to teach others about what they have done to prepare for fallout and why. Training curricula for existing volunteer networks (eg, MRC, Community Emergency Response Teams [CERTs], and Neighborhood Watch Program [NWP]) should be updated with radiation basics and fallout protection guidance. In addition, these volunteers can be trained to deliver a vetted localized nuclear readiness presentation to groups and organizations throughout the community. After an incident, MRC, CERTs, NWP, and other volunteers can also perform key support roles such as reading pre-scripted messages as part of “rumor control” hotlines (Task 4.4) or greeting people who arrive for monitoring and decontamination at community reception centers (Task 6.8).35

Task 2.5—Periodically evaluate progress toward preparedness outcomes and make revisions to improve the public education program over time.

As with any education initiative, progress toward the goal of preparedness should be assessed and the public education program restructured as needed.34,36 Jurisdictions are encouraged to perform a baseline assessment of the public’s knowledge about the effects of a nuclear detonation, the public’s awareness of protective measures, and individuals’ level of preparedness. This inquiry can also help officials to identify factors that could impede people from taking protective actions and to collect information on trusted spokespersons and preferred means of receiving messages for various population segments (eg, Spanish radio station, internet, TDD for the hearing impaired). Later, survey questions can be repeated to test the effectiveness of the education program. Assessments may also rely on focus groups or organization/community exercises. Program effectiveness should be based on actual preparedness outcomes, such as an increase in knowledge of which types of buildings offer the greatest protection, rather than measurement of the number of times a particular training was given or the number of flyers distributed.

*For more detailed instructions on gathering supplies to support sheltering-in-place, individuals and families are encouraged to consult the Ready.gov and American Red Cross websites on basic emergency provisions. Businesses, schools, and organizations are similarly encouraged to adopt the Red Cross Ready Rating Program (http://readyrating.org) to evaluate and improve institutional preparedness, which includes acquiring and maintaining adequate emergency supplies.

Checklist Action 3: Assess Shelters

Enable all building owners and operators—from individual householders to skyscraper managers—to assess shelter attributes and to teach others.

Given the central role of shelter in preventing fallout exposure, it is important that people become more aware of the protective attributes of the structures in which they and their families spend a majority of their days. A national study of human activity patterns in the U.S. suggests that people spend an average of 87% of their time in enclosed buildings and about 6% of their time in enclosed vehicles.37 On average, a majority of people (90%) are found in their residences from about 11 pm to 5 am; schools, public buildings, offices, factories, and malls or stores are frequented mostly between 7 am and 5 pm.37 Building owners and operators—across commercial and residential sectors, and privately and publicly owned properties—have the responsibility to be key educators in advancing the public’s familiarity with places that promise the most protection against radioactive fallout.

Tasks

Task 3.1—Disseminate a shelter rating guide to commercial building managers, enabling tenants and their employees to learn about fallout protection in the workplace.

The protective factor from radiation varies among building types and among different locations within buildings. Basements, the cores of large multistory buildings, and underground parking can generally reduce doses of radiation from fallout by a factor of 10 or more and are significantly better areas for shelter than the ground level and exterior rooms of buildings or areas near rooftops.6 By providing easily accessible and useful information on the best places to shelter (see How to Use Buildings as Shelters Against Fallout), proper sheltering can be incorporated into workplace disaster planning and reduce employee exposure to radiation. Some federal buildings, such as the Hubert Humphrey Building, which serves as the headquarters of the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) in Washington, DC, have posted signage to designate shelter-in-place locations for their employees. Building safety managers should ensure that any sheltering locations predesignated for other hazards also provide adequate protection from radioactive fallout. Businesses and organizations, too, should also plan for the storage of emergency supplies.

Task 3.2—Rate public buildings in terms of their performance as fallout shelters and equip with signage that designates top safety spots.

Designating large public buildings, such as a library, school, or post office, as a public shelter may be necessary in areas where other buildings do not provide sufficient protection (eg, neighborhoods with wood-frame houses or single-story buildings with no basements). Planners should evaluate neighborhood and commercial areas to determine which public shelter designations are needed in advance of a nuclear attack.5

Task 3.3—Partner with schools to expand their emergency plans to include fallout protection and to communicate these plans to parents.

On any given day, more than 1 out of every 5 people in the U.S. is located in a K-12 school—as a student, a teacher, other staff member, or volunteer.38 Emergency professionals should reach out to these centers of social life and convey the importance of incorporating fallout protection into standing emergency plans. Issues to address include determining building and interior locations that provide the best shelter, maintaining supplies to sustain residents for at least 24 hours, and communicating with parents and guardians about preparations. Following disasters, when parents have been asked what was important to them, they have replied that knowing about the safety and whereabouts of their children was their top priority.38 Addressing people’s needs to know whether their loved ones are safe and how to reunite with them will be central to successful sheltering education. Parents and guardians will need solid information from administrators that adequate preparations are in place and that automatically retrieving children from school following a nuclear detonation could endanger both the adults and their dependents by exposing them to outdoor radiation. Jurisdictions also need to develop and publicize their plans for family reunification following a nuclear detonation. Similarly, school plans must address how they will care for unaccompanied minors in the event that caretakers do not arrive.

Task 3.4—Distribute a shelter rating guide to homeowner and tenant associations to build neighborhood awareness about the protective factor of a home.

Community associations connected with all housing types (eg, single-family units, mobile homes, condominiums, and apartments) can serve as conduits to equip heads of households and their families with information that permits them to judge the protective quality of their residence and, if need be, to identify an alternative sheltering location. Educational materials tailored to local residential building trends may prove beneficial given the differences in housing structures across U.S. regions. In the Northeast, more than one-third (38%) of all households live in apartments, a majority of which are located in buildings 7 stories or taller.39 In the South and West, only 2 of every 10 single-family units have a basement (either full or partial), in contrast to 87% of such units in the Northeast and 76% in the Midwest.39

Checklist Action 4: Prepare Warnings in Advance

Strengthen the region’s ability to deliver actionable public warnings following a nuclear detonation through well-chosen technologies and organizational procedures.

In the nuclear terrorist context, effective public communication is essential to saving lives, reducing injuries, relieving distress, and keeping fears in proportion to risk. Community preparedness for fallout must include advance preparations for the effective release of public warnings and guidance in an actual incident. In a nuclear detonation, the communications infrastructure normally used to disseminate official warnings will be degraded. Contingency plans must account for these material impacts and incorporate redundant means of disseminating key messages. Also, public communication strategies should be grounded in what is currently known about the social and psychological processes that people go through from the point of first hearing a warning to acting on the information.40

Tasks

Task 4.1—Develop pre-scripted, pre-vetted, and scientifically based fallout warning messages tailored to the specific needs of the community.

Effective fallout warning messages about protective actions during the immediate response phase should be a jurisdiction’s top priority because of their life-saving potential (although a community’s information needs should be anticipated for all phases of the disaster). It is just as important to communicate to people who are not at risk of fallout exposure as it is to those who are. Unnecessary evacuation impedes logistics and strains resources necessary for those living in high-risk areas. Information gleaned from properly conducted education campaigns (see Action 2) and technical knowledge of the community should be used to tailor these warning messages for the unique circumstances for each area. The format of an effective generic warning message (one that maximizes the listener’s likelihood of taking appropriate actions) is summarized and then modeled in Formula for Writing an Effective Message for Postdetonation Public Warning.41 Sample Fallout Warning Messages for the Post–Nuclear Detonation Period, includes fallout warning message templates developed by Los Angeles County.22 Communities are also encouraged to review key public messages crafted by a multidisciplinary group of technical experts and practitioners for the first 72 hours following a detonation.42 These messages are undergoing further refinement, so jurisdictions should watch for updates. FEMA is currently developing several short videos that can be disseminated after a nuclear detonation. Postdetonation messages should be consistent with the information delivered during pre-incident education.

Task 4.2—Address organizational issues related to effective warning dissemination (eg, who can “trigger” a public message and when).

In the context of a nuclear detonation, providing rapid public warnings about protective behaviors is critical because the fallout hazard is greatest in the early minutes to hours following the explosion. Some jurisdictions lack written procedures on “who” is authorized and responsible for activating a public warning protocol.43 Similarly, plans often fail to document criteria that should trigger the release of public warning messages.43 These omissions can lead to costly delays in notifying the public. Therefore, written plans and procedures for a nuclear detonation should document the role(s) authorized to activate the public warning protocol as well as the criteria that will be used, and they should outline local/regional contingency plans in the event the local Emergency Operations Center (tasked with issuing messages) is nonfunctional. Triggering criteria, for example, could include the primary sources of data (eg, using local meteorological forecasts rather than awaiting federal mapping [see Action 5]). Just as criteria need to be established to trigger initial warning messages, jurisdictions should also determine what indicators will lead to a change in warning message content. For instance, a drop in radiation levels and removal of debris from the roadway may trigger the change from a sheltering message to an evacuation message for certain areas.

Task 4.3—Devise low-tech, redundant means for issuing public warning messages, assuming a degraded telecommunications infrastructure.

EMP effects and the surge in information demand will severely strain surviving telecommunications infrastructure, throwing up barriers to the dissemination of public warning messages. Thus, plans should include lower-tech means to communicate warnings (eg, radio broadcasts, megaphones, 2-way radios, National Weather Service warning radios, amateur radios, loudspeakers, sirens, alarms, PA systems) to augment usual means. For example, the Indian Ocean tsunami and the Haiti earthquake highlighted the importance of radio broadcasts after extensive infrastructure damage and disruption. The use of cell phone texting—which may be available the farther one gets from ground zero—has also been found to be very effective in some disaster settings because it does not require very much bandwidth. Authorities should plan to use any and all communication means at their disposal following a detonation.

Task 4.4—Plan to establish hotlines for an acute demand for health-related information; monitor for rumor control.

Plans should be in place for establishing emergency call-in banks that can deliver pre-scripted messages and dispel rumors. Some people may not be able to access these resources for some time, but many people outside affected areas will need reassurance that they are not in harm’s way. Rumors are a normal indicator of people’s urgent need to gather and confirm useful information during ambiguous situations, particularly those with a safety element, and they become intensified in the absence of meaningful, authoritative information.44 Emergency professionals thus should review callers’ concerns and monitor both “old” and “new” media (see Task 4.5) to act swiftly in correcting misinformation and in refining public messaging.

This is especially important with social media that can instantaneously propagate information. For example, in the aftermath of the 2004 tsunami, a tsunami warning was circulated in Indonesia, only to be revealed as an anonymous hoax.45 More recently, a fake Short Message Service (SMS, also known as text messaging), purporting to be from the BBC, warned that radiation from the Fukushima nuclear plant had leaked beyond Japan and that people should start taking precautions; reportedly this message frightened many in Asia.46

Task 4.5—Monitor public peer-to-peer communications to enhance situational awareness postdetonation and to refine official warnings.

In disasters, people no longer rely exclusively on official sources and traditional media to find useful, credible information. Some individuals are turning to community websites, social networking sites, personal blogs, public texting systems like Twitter, and photo and mapping sites to gather and disperse helpful information and to coordinate a broader response to disaster.47 For example, some residents who wanted timely, local news during the 2007 California wildfires relied on the Twitter postings of 2 men who compiled reports from friends, monitored news broadcasts, and snapped firsthand photos of their surroundings. The men aggregated this information to provide rapid updates about evacuations, meeting points, and places to gather supplies.48

The use of social media in a disaster, however, is an emergent phenomenon. Some disaster research suggests that while younger people may rely greatly on internet-based communication, older adults making decisions about evacuations typically do not—at least not yet. Planners should be aware of these new, citizen-generated flows of crisis communications, tap into them to enhance situational awareness postdetonation, monitor them to refine official warnings and messages, and take proactive measures to develop their own social media capabilities.

Checklist Action 5: Build a Fallout Mapping System

Establish a rapid system for mapping and monitoring the dangerous fallout zone to specify which residents need to take what protective action.

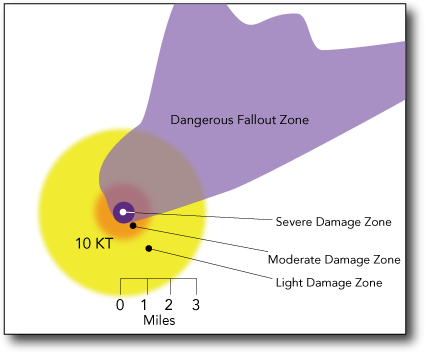

Rapidly determining the DFZ (an immediate health threat) and the wider area of contamination will be critical to guiding the public and responders on protective actions. Larger radioactive particles will settle out within 1-2 hours of the nuclear detonation, creating the DFZ footprint.5 Identification of the DFZ perimeter should occur within the first hours of the detonation to guide response planning and strategies for an informed, delayed evacuation.22 On-the-ground federal support may not be available for 24 to 72 hours or longer, so local jurisdictions should plan in advance to characterize fallout deposition and radiation levels on their own at the outset.5 Until detailed measurements are obtained, the DFZ can be conservatively defined as extending 20 miles downwind in a keyhole pattern6 (see Figure 1). This rough sketch can be refined once modeling of the fallout plume becomes available and actual dose readings from the ground are taken. (Some jurisdictions are prepared to do this on their own, while others will rely on a federal agency like the Department of Energy [DOE]) Knowing the actual fallout footprint and radiation dose levels can vastly improve guidance about where to locate response staging areas, which residents need to evacuate, how soon, which routes present the lowest possible dose, and when and where residents may eventually return.

Tasks

Task 5.1—Develop relationships in advance with federal partners; plan to integrate their contributions to fallout mapping and radiation measurements.

Before an incident occurs, local jurisdictions should contact federal partners with radiological assets and solicit their help in developing nuclear response plans. (See NCRP Report #16522 for a list of federal resources and activation times.) Ideally, jurisdictions (or their states) already have good working relationships with regional all-hazard federal partners such as FEMA Regional Administrators (RAs), DHHS/Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR) Regional Emergency Coordinators (RECs), and DOD Defense Coordinating Officer & Elements (DCO/E); such partners may be helpful in directing jurisdictions to relevant resources. Jurisdictions located in states with nuclear power plants can also reach out to state agencies that already partner with many of the key federal agencies involved in radiation events.

Nuclear response plans should include procedures for integrating federal resources and establishing a bidirectional flow of mapping and monitoring information. Fifteen minutes to an hour after a nuclear detonation, for instance, the Interagency Modeling and Atmospheric Assessment Center (IMAAC)—led by DHS and supported by DOE—will start to provide plume and fallout projections to federal, state, and local authorities, thus helping to guide radiation monitoring and to identify at-risk populations.5 IMAAC maps and predictions will be refined as local field data become available over time. Additional DOE assets—Radiological Assistance Program (RAP) teams and Federal Radiological Monitoring and Assessment Center (FRMAC) resources—will also start to arrive 24 to 72 hours after the blast and provide assistance with actual radiation measurements.

Task 5.2—Conduct a regional inventory of monitoring staff, equipment, dosimeters, and personal protective equipment; plan for a surge in demand.

Following a nuclear detonation, radiation detection equipment and trained personnel will be in high demand over a broad geographic area. Thus, prior to an incident, jurisdictions throughout the region should assess numbers of trained staff, dosimeters, and radiation detection and monitoring equipment; coordinate the purchase of additional equipment (when feasible); standardize staff training programs; and standardize radiation exposure policies across the region.22 At-risk regions should be prepared to use radiation detectors with high-dose rate capabilities. (For additional technical guidance on detection systems and calibration requirements, see American National Standards Institute [ANSI],* NCRP Commentary #19 [2005],49 and Federal Planning Guidance for Response to Radiological and Nuclear Threats [2010].5) To overcome anticipated staffing deficits, at-risk jurisdictions should develop mutual aid agreements with neighboring urban centers and states for sharing radiation health personnel; develop just-in-time training for formal and volunteer responders; have protocols ready for incorporating federal personnel; and recruit and register radiological health professionals into existing volunteer programs (also see Task 1.3).

Task 5.3—Develop plans for synthesizing diverse data scattered across the region to render an accurate picture of fallout distribution.

As noted above, key decisions such as if, when, and who to evacuate will rest on good understanding of the fallout footprint. Various inputs could help construct this broad operating picture: plume projections from federal or other sources; visual observations of the fallout cloud and its downwind drift; discernible fallout particulates that look like fine, sandy material near the detonation; and, most important, actual radiation measurements from the field.5 At-risk jurisdictions and neighboring communities should jointly plan to incorporate diverse data points into a fuller understanding of the dangerous fallout zone and to distribute information, maps, and displays to emergency operations centers throughout the region.22 A region could establish a network of “plume tracking groups”—that is, people who are practiced and exercised in compiling diverse plume data and in knowing where to seek information while working their way up to the best quality materials, likely to be available last. Information must be updated sequentially as more radiation readings are obtained and because of the rapid drop-off in levels of radioactivity over time. Planning should also address how fallout data will be combined with infrastructure damage data to guide staged evacuations.

Task 5.4—Plan for the prompt release of plume maps via broadcast media and social media to reassure the public and support decisions to seek adequate shelter.

Because images are powerful communicators, plume maps should be released without delay, to alert people to the presence—and, equally important, the absence—of a risk; to prevent possible exposure to fallout; and to avoid self-evacuation when it is unnecessary and when it may be harmful. Indeed, as part of pre-incident public education, it will be useful to show what a plume map looks like so people will be familiar with their meaning in an actual incident. Planners should also note that Doppler weather radar may be able to follow the fallout cloud; thus, it will be important for officials to work with television stations in advance to tap this resource as part of the region’s plume mapping endeavor and to train producers, meteorologists, and broadcast announcers in how to put out statements in the interest of the public’s health.

Task 5.5—Pre-position a network of automated radiation monitors to limit human exposure as well as human errors in readings.

Because responders charged with mapping fallout may be exposed to significant levels of radiation, the fewer personnel deployed the better. It would thus be prudent—when economically and technically feasible—to pre-position a broadly distributed network of detection and monitoring equipment that could provide radiation readings automatically to supplement input from roving personnel. Owners of private buildings will be key allies to approach for hosting equipment in technically strategic locations. At this time, there are both technical and financial limits to a “pre-positioned” monitoring system. Such equipment is expensive, and the high levels of radiation anticipated with a nuclear detonation may saturate devices (ie, render them useless).

Nonetheless, some forms of automation are obtainable in the short term. For example, Los Angeles County uses a telemetry system, coupled with a GPS, to automate collection and display of readings on a map of the county to gather situational awareness. Previous nuclear response exercises revealed that responders would be unable to use radios to call in dose readings, as the radio system would be quickly overwhelmed, and that miscommunication was possible between a person giving a field reading and a person recording it on a map at the command center. Following a nuclear terrorism incident, Los Angeles County staff from public health, law enforcement, the fire department, and other cities within the county plan to drive around the county with meters and send measurements over cellular data bandwidth for central plotting and display.50 A rough cost estimate for a telemetry system comprised of 10 instruments and supporting software is $140,000.

*The American National Standards Institute is developing performance criteria for Personal Emergency Radiation Detectors (PERDs). There are two standards:(1) Alarming Electronic Personal Emergency Radiation Detectors (PERDs) for Exposure Control (ANSI N42.49A) are alarming electronic radiation measurement instruments used to manage exposure by alerting the emergency responders when they are exposed to photon radiation; (2) Nonalarming Personal Emergency Radiation Detectors (PERDs) for Exposure Control (ANSI N42.49B) are ionizing photon radiation–measuring detectors that provide a visual indication of the exposure to the user and are designed to be worn or carried on the body of the user.

Checklist Action 6: Plan for a Phased Evacuation

Develop planning strategies and logistical capabilities to support a large-scale, phased evacuation.

Evacuation professionals in the post–nuclear detonation context face a powerful dilemma. They are responsible for helping to relocate people who might otherwise succumb to acute radiation syndrome (ie, people in the least protective of shelters in the most radiation-intense sections of the DFZ23) or other life-threatening circumstances. Yet, these authorities must execute a large-scale, phased evacuation when the transportation and communication infrastructure is in disarray, when a potentially lethal and invisible hazard may be present, and when all survivors have the right to feel as if they deserve to leave first. Recognizing this complexity, this section outlines some preparedness steps that cities can take to improve the chances that, in an actual detonation, evacuation benefits those who most need it and adverse consequences are minimized. Carrying out a mass, phased evacuation in postdetonation conditions will be extremely challenging and contingent upon other capabilities such as rapid mapping of the DFZ. Preparing to execute this protective action is considered the most difficult implementation phase of the Fallout Preparedness Checklist. Comprehensive evacuation planning, according to federal policy, addresses the temporary resettlement of evacuees and the final return of evacuees to their predisaster residences or alternative locations.51 Preparedness for these activities is essential but is outside the scope of this document.

Tasks

Task 6.1—Form regional partnerships and execute mutual aid agreements in support of mass evacuation.

Safe and proper evacuation of a large city requires regional support. Cities should form public health and emergency management partnerships with surrounding areas to address dilemmas posed by a nuclear detonation.

Pre-incident, this collaboration can be used to coordinate region-wide response, assess vulnerabilities, conduct training and exercises, plan for communication, and make modifications to existing mutual aid agreements if indicated. During and following a nuclear incident, the surrounding region can support evacuee movement, provide valuable reception sites to address evacuees with immediate health needs or chronic conditions, and facilitate state and federal assistance.52 Highly coordinated evacuations that include an effective command structure characterized by cooperation among all relevant agencies have been shown to be most effective.53

Task 6.2—Map out buildings and neighborhoods according to how they will perform as fallout shelters.

Rapid identification of people who could benefit from priority evacuation will be among the top response goals (see Tenet 4).5 Selection of priority evacuees can be expedited to save more lives by having already prepared jurisdiction maps to show neighborhoods and building clusters in terms of shelter quality.5 People in neighborhoods comprised largely of single-story, wood-frame houses, for instance, will be exposed to significantly more radiation than those who seek protection in the core of a large, multistory building. Prior knowledge of areas without adequate shelter options can also inform plans for designating public shelters in advance of a nuclear explosion (see Tenet 3).5 Planners should reach out to the private sector to access databases on area buildings, in addition to relying on data in the public domain. Similarly, emergency planners should identify clusters of children and disabled individuals (eg, nursing homes, hospitals, senior apartments) that may require additional assistance in evacuating.

Task 6.3—Predesignate the criteria against which some groups will be selectively evacuated early.

A difficult though vital preparation for a mass, phased evacuation is an agreed-upon framework among regional partners to guide the application of scarce resources in relocating people. Pre-established criteria about who will be evacuated first can help with tough choices in an actual postdetonation scenario, assure that the most lives are saved, and diminish adverse effects associated with mass evacuation. Federal guidance identifies the following life-threatening conditions as warranting early selective evacuation: inadequate shelter in the context of acute radiation exposure, fires and unstable physical structures, critical medical needs, and lack of life-sustaining resources such as water (especially after 24 hours).5 In an actual event, logistical matters such as safe evacuation routes will need to be considered. Mass evacuation can be an extreme solution with many serious consequences. Potential adverse effects include psychological impacts, social distress, and income interruption.54

Officials should therefore reserve its use for life-threatening circumstances or other exceptional circumstances where the benefits clearly outweigh risks.

Task 6.4—Consider how preestablished evacuation routes and transportation options may have to be adapted to the nuclear detonation context.

Predetermined evacuation routes and transportation options that assume an intact infrastructure and a nonradiological hazard, such as a hurricane, would need substantial revision in the context of a fallout plume and blast- and EMP-related damages (eg, debris-strewn roadways, overturned vehicles, no power for traffic signals, loss of public transportation). Comparing preestablished evacuation routes against different fallout plume projections and models of variously damaged infrastructure (eg, certain bridges are out) can provide planners with advance understanding of some of the challenges of moving large groups to safety following a nuclear attack.5 As part of a pre-incident public education campaign, explaining the uncertainties anticipated with a postdetonation evacuation may help reinforce the message that staying inside an adequate shelter and waiting for more information, rather than automatically leaving an area, is the more desirable protective action.

Task 6.5—Craft pre-incident public education materials that share evacuation plans.

Evacuations are more likely to be successful when officials have shared plans with the community in advance and explained alerting methods.53

Pre-incident public education materials should convey when leaving a shelter is appropriate, what relocation plans exist, and how officials will communicate postdetonation. During a mass, phased evacuation, people in different locations will be asked to take different protective actions (“continue to shelter” versus “now evacuate”). Therefore, as part of pre-incident public education, planners should consider preparing diagrams, similar to those that would be used in an actual emergency, that represent different phases of an evacuation. Diagrams will be a critical communication tool in an actual warning scenario; introducing these images pre-incident can help familiarize residents with a phased evacuation process. While some people may not have access to such diagrams during the actual emergency, people in outlying regions where communications are still functioning will be prepared both to see and hear the message that they may be in areas that do NOT need to evacuate.

Some experts caution that raising the prospect of an informed evacuation in advance may confuse people about the principal importance of sheltering. In an actual incident, such confusion might predispose people to leave an area before there is sufficient information on safe evacuation routes or when evacuation is unwarranted because of low radiation levels. Public safety educators should strive to strike a balance between conveying the benefits of sheltering and adequately preparing residents for a phased evacuation.

To balance potentially inconsistent messages about continuing to shelter and preparing to evacuate, public messages might be framed as, “Stay inside an adequate shelter until you receive additional information.”

Task 6.6—Prepare scientifically based templates for postdetonation evacuation messaging.

Preparing evacuation messages in advance can expedite their timely release in an incident and minimize radiation-related illness and death. Effective messaging (such as that modeled in Formula for Writing an Effective Message for Postdetonation Public Warning) helps ensure that only those who should evacuate do. An informed evacuation implies that a person understands both when to leave a shelter and in which direction he or she should go to minimize exposure to radioactive fallout and other hazards.55 Evacuation messages should provide detailed evacuation instructions, including evacuation zones, plans, routes, and/or decontamination centers, as well as specific times and arrangements for certain neighborhoods.56 Messages should also clearly state that certain areas do NOT need to evacuate and that unnecessarily leaving an area could jeopardize others by clogging evacuation routes. Evacuees should understand that they will need to evacuate from their place of shelter and that they may not have an opportunity to go home or reunite with their family first.

Task 6.7—Anticipate that a portion of residents will evacuate independent of government instruction.

Following a nuclear detonation, some people will attempt to escape real and perceived dangers independent of official recommendations and radiation data. Regional evacuation planning should prepare receiving communities for the challenges these self-evacuees may pose. Individuals who spontaneously evacuate a fallout area prior to receiving official instructions may have greater decontamination needs when compared to people who stay in adequate shelter before evacuating.57 Any large-scale evacuation is also likely to have a high rate of shadow evacuation58—that is, departure from areas not officially designated for relocation. After a nuclear detonation, the total evacuee population will likely include injured and noninjured individuals who have been relocated from at-risk fallout areas, plus a potentially large number of shadow evacuees. For example, New York City expects to have to evacuate 300,000 people for health reasons. Yet, receiving communities may also have to face many times that number of uninjured evacuees who still need food, shelter, and medical care for their chronic conditions.58 Out of concern about possible radiation exposure, many spontaneous and shadow evacuees will likely self-report to hospitals in receiving communities.

Task 6.8—Plan to establish monitoring and decontamination centers (ie, community reception centers) for people leaving affected areas and moving to host communities.

Given radiation’s health effects as well as an ability to evoke fear sometimes out of proportion to risk, a nuclear detonation will produce high demand for monitoring of exposure to or contamination from radioactive materials. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in collaboration with many other partners, has produced a guide for state and local public health planners on establishing a system for population monitoring, a core of which is the community reception center (CRC).35

The purpose of the CRC—which may be co-located with other disaster resource sites such as alternative care treatment sites or shelters operated by the American Red Cross—is to assess people for exposure, contamination, and the need for decontamination or medical follow-up. CRCs will play a key role in protecting the public health of people from affected areas and alleviating the anxiety of communities taking in evacuees. Planners should note, however, that past evacuation experience indicates that when people evacuate, they often scatter to nearby friends and family; therefore, not all evacuees will report to a designated shelter or, in this case, a CRC.

Checklist Action 7: Test and Train the System

Integrate, test, and conduct training on the above elements of a comprehensive fallout preparedness and public warning system.

When effective, an integrated preparedness and public warning system enables populations to act swiftly and correctly on protective guidance, thus reducing casualties. Such a system incorporates technical, organizational, social, and human elements.36 A continual process of advance planning, training, exercising, and evaluating are necessary to establish and strengthen linkages among all these elements.59 As jurisdictions move forward through the phased implementation of fallout preparedness actions—from obtaining community support to planning an informed, phased evacuation—the information gathered through the process should be used to update existing plans across phases.

Tasks

Task 7.1—Regularly conduct training programs for emergency personnel, volunteers, and key stakeholders in the community.

Citizens, officials, and emergency personnel should be aware of fallout protection plans and what is expected of them under these plans.60 For instance, citizens should be prepared to seek adequate shelter, and schools should have plans on the books to keep students safe from radiation. Regular training will ensure that current personnel as well as those new to the fallout hazard are familiar with priorities, goals, objectives, and best courses of action.28 The training can also help to identify and address the concerns and information needs of emergency responders and others regarding a nuclear incident.61,62 Everyone—from individual citizens to emergency professionals to journalists (who will be key communicators with the public)—should know where they can get actionable information regarding the fallout plume and evacuation routes. In the case of radiation, a mapping and monitoring group should be trained to compile and produce plume information as soon as possible. These abilities will also need to be tested.

Task 7.2—Exercise, test, and drill all elements of fallout preparedness and public warning systems and include the community in these exercises.

Participation in preparedness exercises enhances perceptions of response knowledge and teamwork.28 Exercises that involve the public serve to inform citizens about the radiation threat, increasing knowledge on what they should and should not do through a more “real” experience.60 Tests that involve multiple agencies also allow these agencies to develop a history of interaction and cooperation that will facilitate their response in the highly complex scenario of a nuclear detonation.60 Exercises should include emergency personnel as well as the private sector, schools, faith-based organizations, volunteers, and other community groups and should be integrated with ongoing pre-incident education programs regarding fallout protection.

Interagency coordination and roles should be among the first aspects of fallout protection tested so that officials have a clear understanding of who is in charge and who is authorized to release messages to the public. A public warning exercise with prepared messages should also be undertaken in early phases of fallout protection planning in order to understand the warning distribution system and how messages will be conveyed in situations such as large-scale blackouts and EMP damage. All exercises should include an after-action report that captures information and lessons learned from the exercise and includes remedial action processes as necessary.28

Task 7.3—Routinely review, revise, and maintain current fallout protections plans.

Fallout protection plans should be considered “living documents” to be revised and changed as new information from exercises, from events, and on capabilities emerge.28 Exercises may indicate that some goals, objectives, decisions, actions, and timing outlined in existing fallout plans need to be reevaluated; operational failures or weaknesses may be identified and need to be addressed in subsequent plans. After exercising the plan, role reassignments and procedural changes may become necessary. Changes in community make-up and resources will also alter plans. As a jurisdiction improves its radiation monitoring abilities, for instance, this may lead planners to reevaluate which information sources have priority for triggering warning messages. Planners should be aware of lessons and practices from other communities that are improving their fallout preparedness plans.

The RRC Approach

Tenets Underpinning this Approach to Fallout Preparedness

Much of what the public knows or imagines about nuclear detonations has been shaped in the context of Cold War science, military strategy, and movies such as The Day After. Many such notions, however, do not apply to nuclear terrorism involving a low-yield explosion in a modern urban setting. Ideas about what constitutes the best protective actions may similarly be based on false premises. This section, therefore, provides a common baseline of understanding in advance of a community integrating fallout preparedness into its larger disaster agenda. It reviews relevant scientific details, operational considerations, and planning assertions that underpin the proposed checklist for fallout protection.

Tenet 1: In contrast to Cold War images of widespread destruction, terrorist-sponsored nuclear threats pose a more contained range of damage and a higher degree of survivability.

-

These guidelines are based on a 10-kiloton ground-level detonation, with no advance warning, as outlined in National Planning Scenario #1.14 Ten kilotons is considered the “approximate yield of a fully successful entry-level fission bomb made by a competent terrorist organization.”15 It is also the scale of the attack outlined in the first of 15 national planning scenarios developed by the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) to support national and local preparedness and to help identify what resources and abilities are needed to respond to a range of terrorist attacks and natural disasters. Many unknowns about an actual weapon, however, have implications for fallout preparedness and response. These include the nuclear yield of the weapon, the device’s location, its altitude above ground, weather conditions, and the time of detonation (ie, during the workday or at night). Such factors determine the potential impact and the populations at risk. The actions in the Fallout Preparedness Checklist, however, are sound and apply to the full range of nuclear detonation scenarios, not just the 10-kiloton context. Alternative scenarios, such as the situation in which a terrorist organization claims to have placed a nuclear device in a city, present additional challenges such as interdiction and are outside the scope of this document.

-

In terms of scale, an act of nuclear terrorism bears no resemblance to a Cold War nuclear attack on the United States. A nuclear war scenario modeled in 1985 assumed 6,559 megatons (6,559,000-kilotons) of nuclear explosives aimed at targets throughout the U.S., and it projected only 93 million survivors, of whom approximately one-third would be injured.16 By comparison, a 10-kiloton groundburst would create an explosion 5,000 times greater than the Oklahoma City bomb.6,17In other words, 10 kilotons is about two-thirds the estimated yield of the atomic bomb (approximately 14 kilotons)18 dropped on Hiroshima—a city that has recovered and is thriving once again.

-

A 10-kiloton nuclear detonation will cause severe damage at ground zero; the damage will then decrease over a distance of a few miles. The initial explosion will produce a blast wave and an intense thermal pulse that will dissipate over a few miles resulting in severe damage within a radius of approximately one-half mile or 10 average city blocks (Damage and Fallout Zones Modeled for a 10-Kiloton Groundburst). Within this severe damage zone, nearly all buildings and structures will be reduced to rubble; few people will survive unless protected by robust buildings or stable underground structures. From 0.5 to 1 mile beyond the blast area, the moderate damage zone will include blown-out building interiors and destroyed lighter buildings.5 In this zone, many people will survive, although many will have significant injuries. A greater number of survivors are expected in the light damage zone, which may extend from 1 mile to beyond 3 miles from the blast area and will be characterized by broken glass and damaged roofs due to shock waves.

-

Most destruction in the damage zones will happen in seconds, leaving people little time to take protective actions. The nuclear detonation will also produce a flash of radiation, with intense light and heat. The immediate (or prompt) radiation generated during the detonation (which is distinguished from delayed outdoor radiation or fallout) could injure people who are outdoors up to a mile away. Fires and serious burns will affect buildings and people up to a mile from the explosion. “Flash blindness” (usually temporary blindness, lasting from several seconds to minutes) may also affect those people who observe the flash of intense light energy—perhaps as much as 10 miles from the explosion.5

Tenet 2: Not all casualties due to a nuclear detonation are destined to happen; those that result from exposure to radioactive fallout can be prevented.

-

Fallout is made of highly radioactive particles mixed with dust and debris, and it can be spread quickly and widely by upper and lower air patterns. The highly radioactive particles that make up fallout are generated when vaporized and irradiated earth and debris are drawn upward by the fireball’s heat and combine with the radioactive fission products created by the detonation. This cloud rapidly rises to an altitude of 2-5 miles for a 10-kiloton detonation, where, under some weather conditions, it assumes a mushroom shape.19 As the cloud cools, highly radioactive particles coalesce and fall to earth, with the heaviest and most dangerous falling first. Fallout will likely be visible as ash, rain, or particles the size of sand, but it may be present even if it is not visible. The distribution of fallout is determined primarily by upper level and surface wind patterns, which often travel in different directions from each other. Because wind patterns are so variable, fallout deposition cannot be predicted ahead of time. Even in real time, fallout patterns are difficult to predict because of microclimates, urban canyon effects, and other complications. Hence, actual measurements on the ground should augment plume models.

-

Fallout poses its greatest health effect in the hours immediately following the detonation, during which time high levels of penetrating radiation can lead to death. The health hazard associated with fallout comes primarily from the human body’s exposure to penetrating radiation (similar to x-rays) discharged from fallout that has settled on the ground and building roofs. Exposure to high levels of radiation over a short period of time can cause acute radiation syndrome, in which people become very ill or die within minutes to months. The Fallout Preparedness Checklist focuses principally on the goal of saving the most lives in the immediate aftermath of a detonation by reducing the chances that people will develop acute radiation syndrome. This can be achieved if people take prompt protective actions against fallout exposure (Tenet 3 and Tenet 4). Outside the scope of the Fallout Preparedness Checklist is the delayed health effect that comes from exposure to lower doses of radiation over time, namely, an increased chance of developing cancer later in life. This delayed health effect is of secondary concern in the nuclear detonation context. In contrast, planning around nuclear accidents—usually slowly evolving events—focuses primarily on the goal of cancer avoidance by limiting individuals’ level of exposure to radiation to “as low as reasonably achievable.”

-

The strength of radiation drops sharply over time and distance from the nuclear detonation. Radiation levels from fallout particles drop off rapidly with the passage of time, with more than half (55%) of the potential exposure occurring in the first hour and 80% occurring within the first day. The most dangerous concentrations of fallout particles (ie, potentially fatal to those outdoors) could extend 10 to 20 miles downwind from ground zero.5 This area is called the dangerous fallout zone (DFZ), which is illustrated in Figure 1: Damage and Fallout Zones Modeled for a 10-Kiloton Groundburst . Larger radioactive particles will settle out within 1-2 hours of the nuclear detonation, leaving behind the DFZ footprint.5 Most people in the DFZ will experience some level of exposure to fallout,7 but a series of decisions regarding shelter and evacuation may vastly reduce their chances of becoming sick or dying from high radiation levels. Outside the DFZ, fallout with lower levels of radiation will be spread up to hundreds of miles away. Radiation levels in this area, known as the radiation caution zone, are not high enough to cause immediate health problems. Nonetheless, protective actions such as sheltering/evacuation, controls on food consumption, and water advisories are warranted to prevent accumulated exposure to radiation that could result in a greater chance of cancer over a lifetime. How the radiation zones shrink dramatically over time is illustrated in Figure 2: Time Sequenced Size of Dangerous Fallout Zone and Radiation Caution Zone (0.01 R/h) for the 10 KT Groundburst Scenario).

Tenet 3: Quickly going and staying inside the closest, most protective building—not fleeing the area—saves lives by minimizing exposure to fallout.

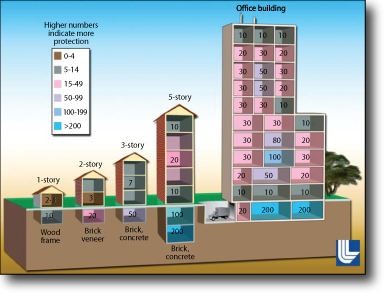

- Sheltering in common urban structures such as large office buildings or underground garages significantly reduces radiation exposure.6,20,21 A building’s “protective factor” (PF)—that is, the level of protection from radiation—is a measure of the structural materials and the distance between people and radioactive fallout.5 The greater the protective factor, the better the shelter. See Figure 3: Sample Protection Factors for a Variety of Building Types and Locations. Dense materials such as brick, cement, and earth provide better protection than wood, drywall, and thin sheet metal. Areas within a building, such as restrooms and stairwell cores, which are distant from deposited radioactive fallout, provide better protection than those close to roofs, windows, and exterior walls. Multistory brick or concrete structures, cores of large office buildings, multistory shopping malls, and basements, tunnels, subways, and other underground areas are examples of good shelters. Many good shelters will also have ventilation systems that should be shut down or segmented to prevent the introduction of radioactive fallout in the building. Examples of poor shelters include outdoor areas, cars and other vehicles, mobile homes, single-story wood-frame houses, strip malls, and other single-story light structures.22 For more detail on protective factors, see How to Use Buildings as Shelters Against Fallout.

-